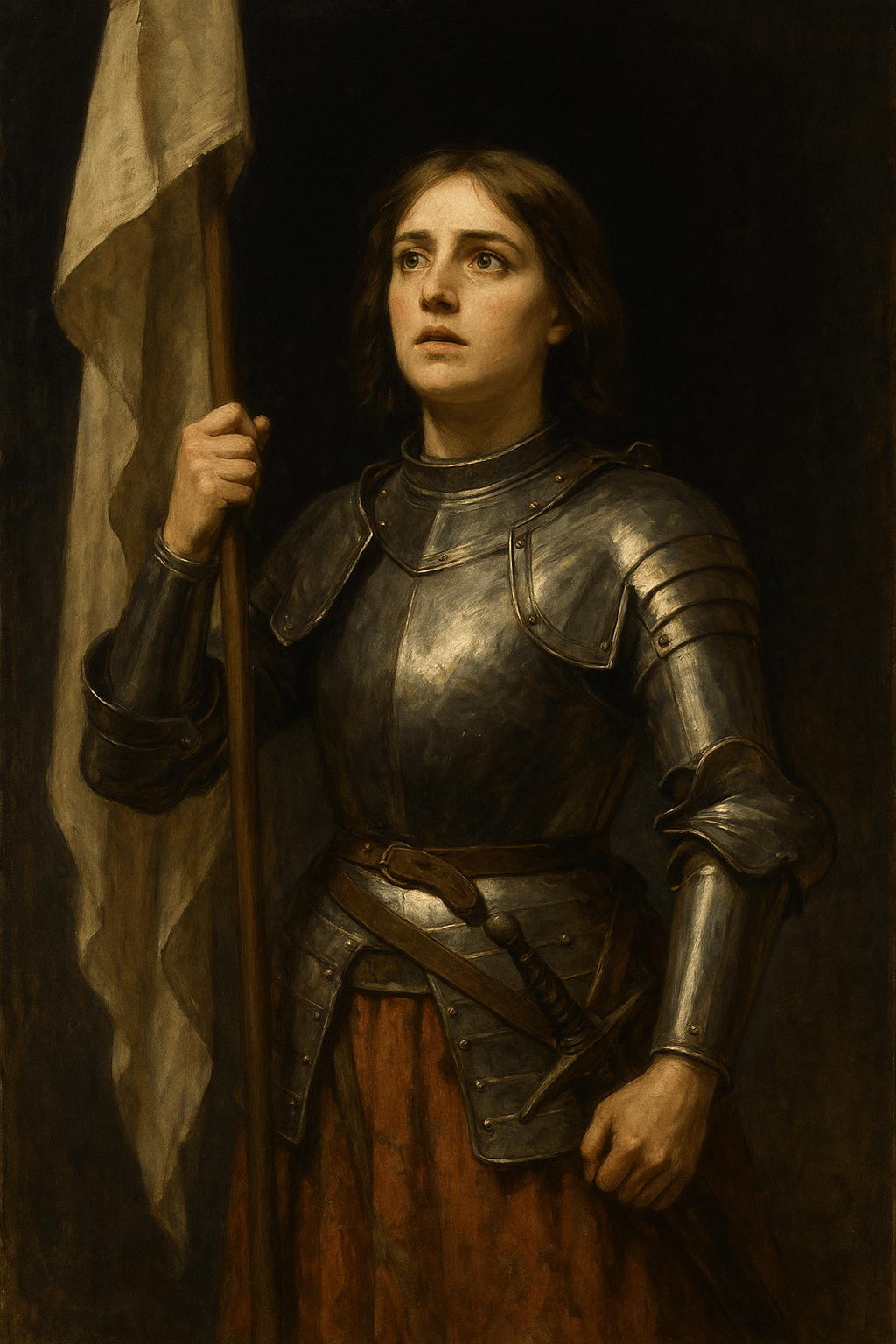

Isabella de’ Medici (1542–1576) was a woman born into the highest reaches of Renaissance power. The daughter of Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, she was not only politically connected but intellectually formidable, known for her sharp wit, learning, and independence. She lived apart from her husband, governed her own household, and moved through the world with a confidence rarely permitted to women of her time.

Her death was sudden and suspicious. Officially recorded as natural, it was widely rumoured that she had been strangled by her husband, with her brother’s silent consent. In the accounts that followed, Isabella was reframed as unfaithful, improper, and ultimately responsible for her own fate. The rumour justified the silence. She became yet another woman remembered not for how she lived, but for how others claimed she failed.

She belongs firmly to the concern of this blog: the recurring cultural pattern in which women who act with agency – women who speak, resist, or refuse – are vilified, mocked, or erased. Isabella was admired in life, but reimagined in death as an example of excess: too free, too proud, too visible. Her historical legacy is less biography than cautionary tale.

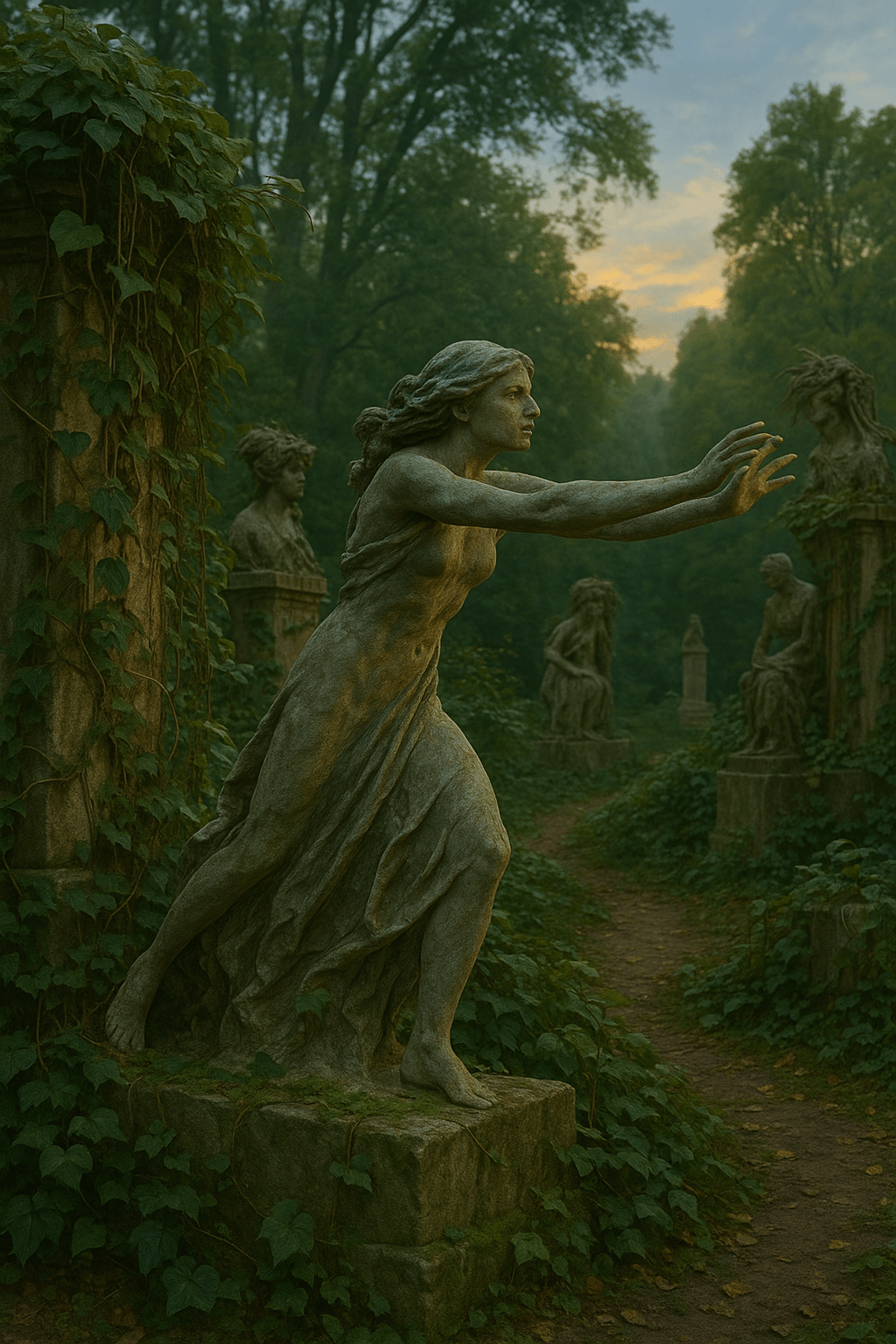

The poem that follows is a fictional act of contemporaneous witness, written in the imagined voice of a woman at court who sees Isabella not as rumour would later paint her, but as she truly was, radiant with presence and danger. The language and structure of the poem are modelled after Gerard Manley Hopkins’ The Windhover, a Victorian meditation on the sudden beauty and power of a falcon in flight.

In The Windhover, the speaker watches the falcon with awe and devotion. Its motion is sharp and sovereign, almost divine. Hopkins uses densely textured rhythm, compound phrases, and sonic compression to capture the force of the moment. His admiration is not mild or sentimental but instead ecstatic, almost spiritual. The falcon becomes a sign of glory, a flash of the sacred in the real.

That same energy of admiration shapes the voice in this poem. Isabella is described as flame-footed and falcon-fine, a figure moving with grace and fire through the space of the court. The language mirrors Hopkins’ intensity, with invented compounds like grace-gaited, steel-point, and coffin-cruel. There is reverence here, but also urgency. The speaker knows this moment will not last. She foresees how Isabella will be turned into a warning. She writes in order to resist that future.

Both poems are, at heart, acts of praise written under pressure. In Hopkins’ case, the pressure is theological – the falcon is a glimpse of divine strength. In this poem, the pressure is historical and political – the woman admired will be brought low, not for failing, but for flying too visibly. In both cases, the poet watches in awe, knowing that the world does not always honour what is most alive.

This is a poem that catches Isabella not in her fall, but in her rising.

To Isabella, in Her Rising

I.

I caught this morn, most morrow-bright,

A flame-foot girl, falcon-fine — she,

Isabella! — in poise, in pace,

Astride her stair as if storm-kin’d, grace-

gaited, fire-forged from the Medici.

What burst of being, in that she!

Heart-jolted, gaze-stung! — gold-writ gown,

And glance so lit

The air about her, lit it, split

My gaze, — not in shame but shine.

Tyrants turn at her tongue; I — mine

Eyes would drink her, word and wit.

II.

They'll say — O see — she was wanton, wild,

Wife too little, mistress styled,

Too loud, too proud, too free in face —

To brand her bright, they’ll black her grace.

Her name, once gold, will grind defiled.

Brothers will nod, and husbands hush —

Her death, a murmur, soft and rushed.

It was her doing, they will say.

But lo — who profits from decay?

Not she. Their peace is bought with hush.

III.

So let me, now, ring her, unblurred:

Bright-branch’d, bell-clear, word-for-word

In verse no steel-point shall unstick.

Though court, coffin-cruel, choke her feet,

My line shall clutch her, quick with breath and bird.

I bind this moment, fast, in sounding —

Not tomb-stone-bound, but tongue-loud bound.

Let men mis-speak her name, must, so,

But not without this fire, this faith's-thrust:

A woman seen, up-sprung, sky-found!

This post is part of Kate Coldrick’s wider body of writing. More of her work can be found at katecoldrick.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.