Camille Claudel (1864 to 1943) was a sculptor of extraordinary power: formally trained, fiercely original, and long unrecognised. In a world that made little space for women to shape stone, she carved figures of tension, intimacy, and raw motion. Her early promise brought her into collaboration and entanglement with Auguste Rodin. For years, she was his muse, model, and partner. But she was also his rival in skill, and often his uncredited co-creator.

Where Rodin was lionised, Claudel was isolated. Critics dismissed her as derivative, though her sculptures revealed a distinct, searching voice. Works like The Waltz and Clotho explore longing, grief, and desire not as abstract ideals, but as sculpted truths in female flesh.

After the end of her relationship with Rodin, and a string of rejections by the art establishment, Claudel grew increasingly distressed. In 1913, she was committed to an asylum by her family, particularly her brother, the writer Paul Claudel. Though doctors stated she did not require confinement, she remained institutionalised for the final thirty years of her life. She died there, largely forgotten.

Today, Camille Claudel’s work is being reclaimed. Her sculptures have been gathered in retrospectives, and her life reexamined as a story not of madness, but of suppression: of what happens when a woman dares to author her own form.

This poem, while honouring Claudel’s biography and artistic spirit, also draws inspiration from the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Rilke admired Auguste Rodin deeply, writing of him as an artist wholly bound to the creative act, someone who surrendered to the Thing he was shaping. In his prose, Rilke sought to dissolve boundaries between artist, material, and form, describing sculpture as something alive with inward force. This influence shapes the tone and movement of the poem. Its rhythm, its sense of stone as breathing and remembering, and its focus on the tension between silence and voice all echo Rilke’s poetics. By turning that language toward Claudel, the poem reclaims its power not to praise Rodin, but to lift the one he overshadowed into view.

This is not just elegy, but invocation. A re-voicing. A refusal of silence. Claudel was not simply a figure behind Rodin’s legacy. She was the one who shaped shadows into form and left her fingerprints in the stone.

The Sculptor’s Silence

(for Camille Claudel)

They said she chipped too deeply,

into muscle, into myth.

That marble was not meant

to carry a woman’s scream.

But within the stone,

a held breath stirred,

a dormant echo,

already yearning for its form.

She struck too close to the gods,

too bold with the chisel.

Her hands, remembering

the earth's first pulse,

what it meant

to coax a world

from its inertness.

They called it madness,

this hunger to carve, not beauty’s shell,

but its raw, trembling ache;

not muse, but the mirror’s brutal truth;

not ornament, but origin’s

dark, insistent root.

The clay itself,

a living plea

beneath her turning thumb.

Rodin stood in bronze,

his shadow cast, a heavy lid.

She, behind doors that held

not merely wood,

but time itself.

Her name, a breath unuttered.

Her hands, now folded, listening

to the silence men had signed.

Thirty years.

Thirty years, where walls became

the hard horizon of her gaze.

She yearned for the clay’s yielding,

for the light’s shaping,

the ache of work;

that true, demanding prayer.

And still:

the stone remembers.

Each figure she left behind

breathes a refusal,

a quiet insurrection.

From within their sculpted form,

a breath, insistent,

rises.

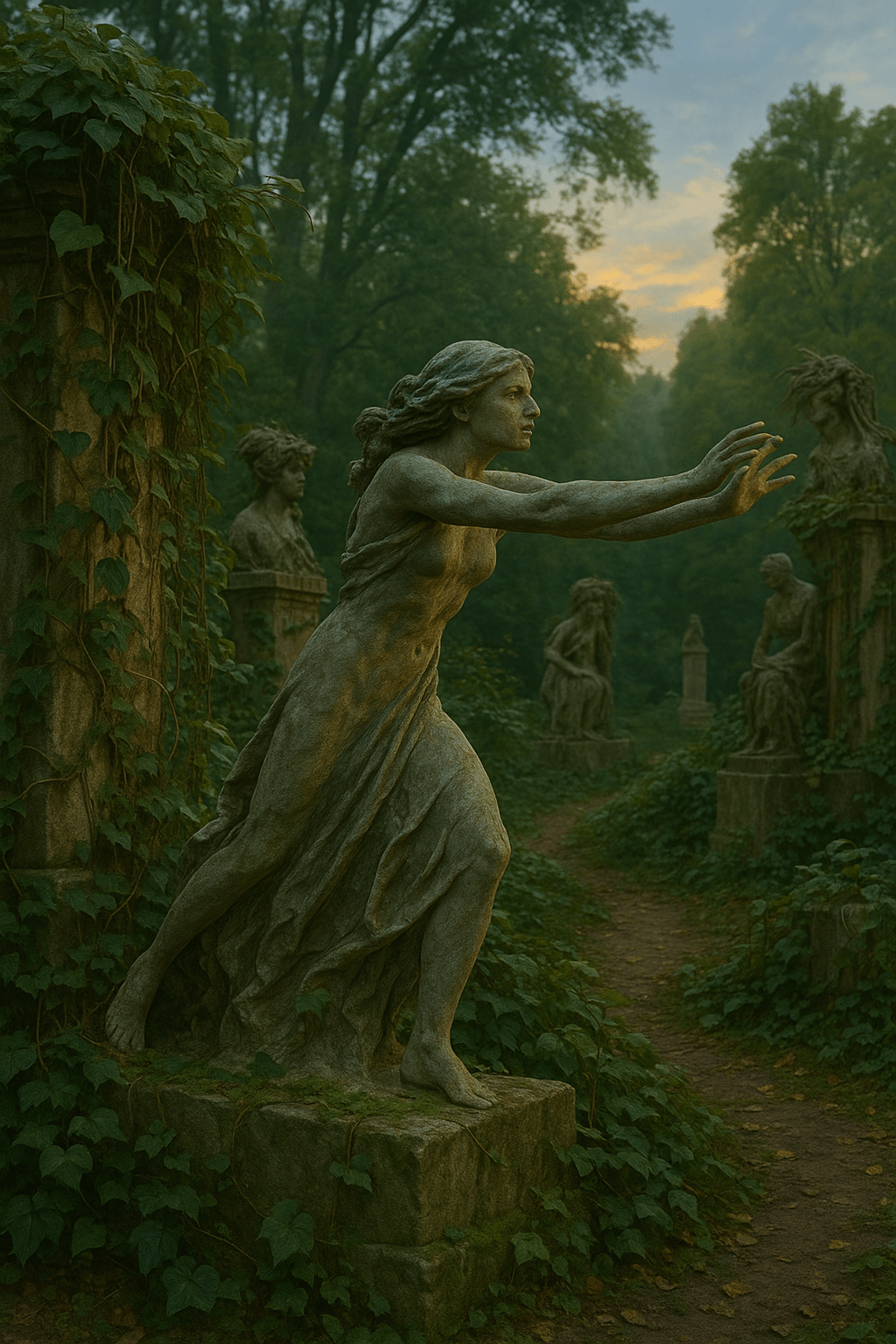

Look:

The Waltz, spun from sorrow’s deep embrace.

Clotho, unravelling time

from a hand’s defiant grace.

A woman in bronze, not waiting

to be touched

but reaching, reaching,

as if the air itself were clay

to seize.

Now, from the hush of museums,

her voice unfolds;

not a whisper,

but the earth’s low, thundered pulse,

a tremor through the ancient stone:

I was.

I am.

I made.

They cannot cast silence forever.

Not when marble holds memory’s

deep hewn form.

Not when the Thing they tried to bind

becomes the voice that speaks,

a living statue,

rising from its past.

Alongside this project, Kate Coldrick also writes about education, culture, and inclusion at katecoldrick.com